Tim Flannery, Adriana Vergés, Rebecca Huntley & Emma Johnston: We Still Need to Talk About Climate Change

We cannot have climate deniers in the parliament because it is an absolute dereliction of their duty to the community to not believe in climate science and say they represent the interest of the Australian community and the future.

Yes we’ve made a great mess of the planet. We’ve caused this problem, but if we caused it we can fix it.

Over the years the two things which I think have worked most effectively for addressing climate change are: focusing on solutions and engaging with emotions.

In January we watched helplessly as Australia burned. Over 18 million hectares were destroyed, and more than a billion animals were killed. It was clear to those on both sides of politics that Australia needed immediate climate action. Flash forward and the all-encompassing nature of COVID-19 has made it almost impossible to talk about anything else, but the imperatives of climate change have not gone away. So how do we restart the conversation on climate?

In Australia, despite the work of our world-leading scientists, climate change is a vexed political topic, rather than a question of science and policy. As we grapple with the new normal of bushfires and water shortages, on top of pandemic recovery, how can we take the politics out of these important issues? How can we bring communities together to think about change? Join climate scientist and author of The Future Eaters and The Weather Makers, Tim Flannery, marine ecologist Adriana Vergés, social researcher, author of How to Talk About Climate Change in a Way That Makes a Difference, Rebecca Huntley and marine biologist and Dean of Science at UNSW Sydney, Emma Johnston to find out how we might turn these pressing climate conversations into climate solutions.

Presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and supported by UNSW Science. This event is part of the UNSW x National Science Week program and is part of the UNSW Grand Challenge on Thriving in the Anthropocene.

Transcript

Emma Johnston: Welcome to We Still Need to Talk About Climate Change, the 2020 Jack Beale Lecture. I'm Professor Emma Johnston, proud Dean of the Faculty of Science here at UNSW. And this event is presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and supported by UNSW Science.

But before I begin today, we're joining you from Bedegal Country, you will be joining us from a range of Indigenous land and sea countries across this vast continent. And I'd like to pay our respects to the people who are the traditional custodians of these lands and seas, and to recognise their continuing connection to country, and a deep knowledge that abides in those connections. I'd like to pay my respects to elder's past and present, and to extend that respect to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who are joining us today.

In January, we watched helplessly as Australia burned. Over 18 million hectares were destroyed, and more than a billion vertebrate animals are thought to have been killed. Simultaneously, the third mass bleaching event in five years was beginning on the Great Barrier Reef, it was clear to those on all sides of politics that Australia needed immediate climate action. But by March this year, the COVID 19 crisis had overwhelmed us and there is no sign of a quick escape from the pandemic and its impact. It has made it almost impossible to talk about anything else. But the imperatives of climate change have not gone away. So how do we restart the conversation on climate? Do we need to change the way we talk about climate change and the environment, so that what we say has more effect? And how do we move from talk to action? To help us answer these questions, we're joined by scientists and authors, Tim Flannery, Adriana Vergés and Rebecca Huntley. These are three people for whom climate change is at the very forefront of their work and their lives. But who tackle the need to talk about climate change from very different angles.

Let me introduce them. Scientist and writer Tim Flannery is one of the world's most widely known communicators about climate change and sustainability. He's a monologist, and a palaeontologist who's described more than 30 mammal species. Tim has combined his scientific career with a substantial track record as a public scientist and a prolific writer, his latest book The Climate Cure: Solving the Climate Emergency in the Era of COVID-19, is due out this November. And as a distinguished alumnus of UNSW. We are particularly delighted to have him with us tonight. Our second speaker, Rebecca Huntley, is a social researcher, writer and broadcaster, and expert on social trends. She's an author of books on food, politics, and education. And as a social researcher, Rebecca has a unique insight into the reality of how Australians think, feel, vote, and behave. Her most recent book is, How to Talk About Climate Change in a Way that Makes a Difference, a fascinating account of how we need to understand human responses to climate change, in order to create effective and collective action. And our third panellist this evening, Adriana Vergés, is an associate professor in marine ecology. She leads a research group here at UNSW that focuses on the ecological impacts of climate change, and the conservation of the world's algal forests and seagrass meadows. She's published more than 80 peer reviewed scientific studies, but is also passionate about communicating science to the wider public via a range of media, and for this work, she was awarded the inaugural UNSW Emerging Thought Leader Prize in 2019. Thanks for joining us, everyone.

I want to open up this conversation with a question to each of you about your thoughts on how we communicate about climate and the environment. And I'll start with Rebecca. So Rebecca, your new book, How to Talk About Climate Change, and in a way that makes a difference, looks at how we should be talking about climate change, but how we should be doing it if we want to reach people and inspire change. So what needs to be transformed? What needs to change about what we're up to? What have we been doing wrong?

Rebecca Huntley: Well, I mean, I could be very cheeky in a room full of scientists and say that we need scientists to stop talking about climate change, keep researching it or get better at talking about it. And we really need every other person in every other profession to talk about climate change. Because we are at a point in Australia and, you know, in, in many, many other countries where, the majority of people agree with the current scientific consensus, they don't challenge it. They agree climate change is a genuine threat, and they want action. But in all the research I do, what is lacking is a real sense that the climate crisis connects with their life and the things that matter to them now. And what that allows politicians to do is say, oh, you know, we're going to do something about climate change. But it's so much more important to do something about cost of living, and the cost of energy, or health, or the future of your children. And they're actually able to push climate change to the, to the farthest reaches of their policy priorities, and make it as if it can be separated. And so connection is actually critical. And that means that, like I said, we've got to think about, we've got to have people of all kinds of professions, all kinds of understanding of the science in all, in all parts of our way of life, talking about how that connection is real, present, and exists to that.

Emma Johnston: Do you think the increasing kind of frequency of emergency states associated with climate change is helping this communication? Is it making those links clearer?

Rebecca Huntley: To some people, yes, but to other people, no. And that's why it's so critical to understand how different kinds of people respond emotionally to the language around climate change. And I saw this with, you know, real sadness and frustration, as I talked to people after the fires that we had over the summer. For those people who were already really concerned about climate. They became more concerned, and it did move people who are already concerned, and it did create a sense of urgency amongst people who thought, oh climate change is important. But time after time, I saw people that said, is this about climate change? Or is this about, you know, environmentalists, or fuel load or what, all the rest of it, they just didn't see the connections, they resisted the connections. Not just because some parts of the media were very disingenuous in terms of how they reported it, we didn't have as much political leadership as we could have. But to see those connections, to really see the summer fires, as what had been predicted for a long time, is such a confronting thing for people. It's chickens coming home to roost. And for those people who are already trying to resist that knowledge, because it's too confronting, too overwhelming. And they also have a complete lack of trust in our leaders to manage this crisis, then it's often very hard to confront that head on.

Emma Johnston: These are really important points. They're quite challenging as well, especially for scientists who are listening. So I'll move to Adriana, who is a scientist, and one of the aspects of your work has been your intent all the way through your scientific research to actually communicate while you're doing your research. What have you learned about what works in terms of engagement around climate issues?

Adriana Vergés: Yeah, so I, you know, because my work is on the ecology and conservation of the water forests and seagrass meadows. Very early on in my career, I realised that people didn't care enough about these habitats, you know. So people care about corals, they care about dolphins and whales, but when you're trying to protect things like seaweed forests, there's a fundamental problem, which is that people don't even know that they're important, right? So if my job is to try and conserve them, I need to, I realised that I need to prioritise science communication, right? So over the years, the two things that I think have worked most effectively, have been focusing on solutions, and engaging with emotions. And the thing about solutions is that, you know, anybody that works as an ecologist, like we are constantly faced with so many stories of environmental degradation, major problems, right? But we are also developing a lot of solutions. And I think that we're particularly bad at communicating those solutions. Which is a problem, right? Because people can’t get empowered and inspired when they're bombarded by my stories of things getting worse. So in my own work, I work on climate change, I also do a lot of restoration work. The restoration work is very positive. It's about fixing a problem. It's about fixing, it's about rewilding the Sydney coastline, because we have improved water quality to a major degree, right? So this is the problem that occurred, that, you know, there used to be a huge sewage problem. We fix this problem, by a major engineering feat and deep ocean outfalls, the water quality is not so good that we can restore and rewild our coastlines and bring back the workforce that used to be here but disappeared. So I chose that project to raise awareness about the importance of seaweed forests. I don't talk so much about my climate change research that shows that they're disappearing so fast, because I think people, you know, they're already worried about, you know, the loss of corals, and I don’t think I'm going to engage them about the importance of seaweed forests, if I tell them, you know, what, it's not only corals that are suffering, it's also kelp, you know, there's a point where people can engage. So focusing on solutions and actually doing science that can deliver those solutions. That's one thing, and the other one is about engaging with emotions and, and to do that I collaborate with artists. So a lot of my outreach involves working with two main artists, Jennifer Turpin, and Michaelie Crawford. And we've done a series of, kind of, big scale events, like Sculptures by the Sea, Outdoor Exhibition, events that aim to connect people with nature, and raise awareness that way, through getting people to feel something. You know, if I tell you that, you know, we've already experienced one degree of warming, and we're losing 90% of our giant kelp forests. I think that doesn't stick. But if you can create an artwork that makes people feel something about that, that will stay with them. I think.

Emma Johnston: So connecting them to what they might be losing.

Adriana Vergés: Exactly. Yeah.

Emma Johnston: So it's interesting, because you're talking about baselines that we're forgetting, but as much as we forget what we had in the past, that was good. We also forget what we have in the past that was bad. And the solutions that we've actually developed along the way.

Adriana Vergés: That's right. Yeah.

Emma Johnston: So we forget the stinking Sydney Harbour.

Adriana Vergés: That's it.

Emma Johnston: And, you know, the terrible pollution problems that we had in the 70s.

Adriana Vergés: Yeah. We actually, we did a survey and we asked Sydneysiders, do you think the water quality in Sydney is getting better or worse? And this was in connection with an artwork, but 60% of people thought it was getting worse. You know, when instead, you know, there's been a dramatic improvement. You know, so we've just been so bad at making some noise about fixing this major problem. And yeah, I mean, I find that when people hear about these positive stories, and when you give them the opportunity to be a part of that they respond really positively.

Emma Johnston: Fantastic. Well, Tim, you've been telling stories about climate change for a long time now. I'm not saying anything about how old you are. But I can remember reading some of them, the very early ones, and one of the first to focus on climate, I think was 2005. So you've definitely been talking about this topic for a long time. How is what you're speaking about, and the way that you're speaking about it in climate communications changed over that period?

Tim Flannery: Wow, well, things have changed simply because the climate science itself has moved on. And I think when I started on this journey, you know, in the late 1990s, early 2000s, for a lot of people, climate change was a theoretical something. They hadn't necessarily experienced impacts in their own lives. Whereas today, you go out to regional Australia, particularly to farmers, or to people in the regional communities, and their lived experience is one of climate change. And that is both, it's useful in terms of, allowing people to understand more what this enormous change is about. But of course, the impacts are catastrophic. So, and the solutions are often difficult. So that's how it's changed, I guess for me, it's gone from a theoretical contract to a lived experience. And I'm quite concerned honestly about the impact on the mental state for many people, particularly younger people who see this despair, they see things not changing. And I guess increasingly, I'm trying to turn to, as Adriana says, to solutions, to some sense of optimism. Because yes, we've made a great mess of the planet, we've caused this problem. But if we caused it, we can fix it. We know that. And so that sense of optimism and opportunity for everything from entrepreneurism through the greater care of our planetary systems is really becoming a central theme, I think.

Emma Johnston: So that actually helps if we understand how substantial our effect on the planet is because if we know how substantial it has been, we can know how positive it could be if we spin it round.

Tim Flannery: That's right. We think we're living in the Anthropocene, we created it surely, we should be something we can thrive in.

Emma Johnston: Yeah. And looking at previous cultures. I think, one of your first books, The Future Readers, oh, one of the first that I read, was all about how we transformed entire ecosystems very much prior to when we started burning a huge amount of carbon, we still managed to have an impact.

Tim Flannery: Yeah, people don't realise just how influential as a species, we've been over 10s of 1000s of years.

Emma Johnston: Now, one of the fascinating arguments that does come from Rebecca's work on climate change is that we need to bring emotion into the conversation. And we've had, we started to talk about that. But one of the quotes is, now that climate science has been proven to be true to the highest degree possible, we have to stop being reasonable and start being emotional. More science isn't isn't the solution. People are the solution. So happy Science Week. But first of all, Adriana, as a scientist, who is also a communicator, how hard do you think this is for most scientists, you've kind of broken through that barrier. But how hard is it for them to step out of the framework that they've been brought up in and trained in, that is one that very much says, remove emotion from your work. How do we get more of them to step out and start talking?

Adriana Vergés: It's really, really hard. Yeah, I mean, we're trained, you know, the, we communicate with data, facts, graphs, statistics, that either you know, prove or disprove hypotheses, right? The way I've done it, in terms of connecting with emotions, is by collaborating with artists, filmmakers, you know, that any kind of art, I think works.

Emma Johnston: So you let them do some of the talking, is that right?

Adriana Vergés: Yeah, or they, you know, I ask for their interpretation of the facts. I think when it comes to marine ecology, it's also about bringing it from, on the water, you know, to above water for people to see, you know, because how can you care about something if you don't even know what it looks like, right? So I put a lot of effort into into filming what we do, and actually showing, you know, photograph is worth more than 1000 words, you know, every graph can actually be also shown with, you know, the results of the graph, you can actually also show them with a photograph or a video, and that is so much more compelling. So, yeah.

Emma Johnston: And more beautiful. Rebecca, this, this was one of your statements. So I'm just gonna…

Rebecca Huntley: Yes, and I do want to say that I'm not saying that science departments should be defunded, although the current federal government perhaps has gone some way towards doing that in the recent, recent past. I'm not saying that at all. What I'm saying is that I think that the science in and of itself, it only gets us part of the way. The larger question, and this is where all kinds of people outside science, and every profession has to step up and tell stories, make connections, because for a long time, climate scientists, like Tim, have been doing that heavy lifting, you know, in terms of that communications task, and we just need multiple voices, we need so many voices in our society that the politicians who are getting in the way of progress can no longer ignore them. They’re quite good at ignoring scientists, been doing it a bit more in the pandemic to better effect, but they're quite good at ignoring academics. But they really can't ignore people from the insurance industry, from the finance industry, from, they can't ignore farmers, they can't ignore faith leaders, if we all speak out in support of what the science is telling us and what the solutions can provide us.

Emma Johnston: And that's another spin on it, isn't it? Rather than everyone becoming emotional, per se…

Rebecca Huntley: Yeah.

Emma Johnston: It's everyone using their own evidence base or seeking out an evidence base…

Rebecca Huntley: Exactly.

Emma Johnston: To communicate what's happening in their own words, and in their own terms.

Rebecca Huntley: That’s exactly right.

Emma Johnston: Ways that have meaning for other people.

Rebecca Huntley: Yeah, making that really, kind of, meaty connection, and also speaking, really to multiple audiences. So one of the really striking things in the climate research, climate opinion research, is one of the big distinguishers about whether you believe climate change is real and how urgent you think it is, is your education status. So in a sense… and in terms of trusted messages, the more educated you are, and the more alarmed you are, the more that you do listen to academics and climate scientists. But if you're disengaged from the issue, or you're cautious about it, you want to hear about it much more from your friends, your family, perhaps your employer, perhaps people in your local community. So it's not about saying get rid of science, get rid of scientific research, or get rid of scientists talking about it. It's about we need an army of communicators.

Emma Johnston: Adding voices.

Rebecca Huntley: Exactly.

Emma Johnston: Thanks Rebecca.

Rebecca Huntley: You know, only for a moment, not only because I'm slightly, you know…

Emma Johnston: Outnumbered.

Rebecca Huntley: Outnumbered on this panel by scientists.

Emma Johnston: No, it's great to have this perspective. So, you mentioned again, the pandemic and I started by saying that the pandemic has made it difficult to talk about anything else except the pandemic. It's also got potentially some silver linings in terms of the way that behaviour has changed so quickly in the way that we've shown our collective action is so powerful. And we've also had scientists up there getting national television every day, up there, you know, speaking out, all of those epidemiologists have popped out of their labs and their and their front page news. So, Tim, you're writing a book about this? What can we learn from the crisis? How can we emerge stronger on climate?

Tim Flannery: Well, you know, Emma, I think the greatest thing that the pandemic has shown us from a climate perspective, is that, what was considered to be the economically impossible, the politically impossible, in fact, is possible, when you know, you need to do it, you know. So that is a very valuable lesson. So we don't necessarily believe people who say, No, it can't be done, you know. But the other thing that it has shown us is that the way you deal with an emergency is pretty structured. And it doesn't matter whether it's a climate emergency, or it's a pandemic, the same steps have to be followed and, and you know, the first, the first step is to stop the increase of the problem. And I suppose for the pandemic, that was to, to bring in some social isolation, so the chain of infections slowed down. For climate change is just about cutting those emissions. That's the first essential step that you need to do in both cases, and that, short, sharp, and hard, but possible. And then you need, you need an emergency room to deal with all of the casualties, because we're quite far into both of these, these crises. So you know, that means for the COVID pandemic, having sufficient emergency spaces in hospital and sufficient staff, and PPE and all the rest of it. For climate change, it means having the right sort of policies in place to know where the damage is going to hit, which parts of our coasts are going to be hit by rising sea levels first, what are the appropriate policies to make sure we don't, we can minimise that damage. Do we have enough, again, capacity in our medical systems and emergency services to deal with the heat waves and the fires and everything else, so that planning is really, really important. And then finally, the most difficult bit, arguably, is to search for a vaccine, for something that will really deal with the problem. So we know with COVID, that search is going to cost billions of dollars and potentially take years, you know, but it's worth pursuing. For climate change, the vaccine really is going to be about drawdown, it's going to be about getting some of the gas out of the air by treating our planetary system much better than we are today. Looking after our forests, looking after our oceans, enhancing some of the processes that allow Co2 to be drawn out of the atmosphere. And that's a project that will take billions of dollars and many years. But it's really essential, because without it, we will trigger, almost certainly now, I think, tipping points that will drive the problem into ever more severe territory.

Emma Johnston: That's a fantastic analogy. So we're pretty much at the stage four lock down on emissions straight away as soon as we can.

Tim Flannery: Absolutely. That's where we need to be, stop the problem proliferating.

Emma Johnston: And then, work it from there. So we do have some questions coming in from the audience. And I'm going to start asking a few and spreading them out. So the first one is, despite the recent bushfires, Australia still has the third highest rate of climate denial in the world. How do you convince a denier, if these disasters can't. Rebecca.

Rebecca Huntley: I might respond to that. Yeah. So it look, it's interesting. Most surveys put climate denial in the community at 10% or less, and there's probably about another 10% of what I would call denial lite. So not full fat deniers, they're kind of people who think that, you know, they're kind of doubtful, but so doubtful that you that, you know, they're there probably the only difference I find in in my research between a genuine denier and somebody who's doubtful is that the people who are doubtful still believe the CSIRO, and the people who are deniers think the CSIRO is a cabal of left wing people that couldn't get a job at the ABC. But, I think I actually don't think the percentage of people who are deniers in the community is the problem. The percentage of people who are deniers and in the parliament are a problem. And the percentage of people in the media that pretend that they are speaking for a much larger percentage of the population, that's the problem. Because what those people in power are doing is amplifying the sense that denial is bigger in the community, and that it's a legitimate position to hold, and that it puts, particularly journalists and media, you know, media organisations in this bizarre situation where they think they have a denier and a climate scientist on a panel, and that's balance. So I actually think that we're probably never going to do that much about the percentage of people who are deniers in the community. And we probably don't have to, because if you can convince them on the solutions to climate, the need to move to renewable energy, the need to have clean air, and clean soils, and clean water, which you can do, you don't need to convince them on the climate science. But you do need, we cannot have climate deniers in the parliament because it is an absolute dereliction of their duty to the community to believe in climate science and say they represent the interests of the Australian people in the future. So I think that we have to be strategic about where we focus our energy on denial. Now, that question leads to the role of let's say, News Corp and Rupert Murdoch's media empire, why is it that Australia and the United States are two areas where we have, you know, larger percentages of climate denial than elsewhere? I'll leave that for other people to comment on. I’ll stop speaking now.

Emma Johnstone: Adriana?

Adriana Vergés: Yeah, I'm not sure I can comment on Murdoch and whether or not he is taking over the world. Yeah, I mean, I don't know why, I'm originally from Spain, and in Europe, in general, it's a very different conversation we're having. So for me, it was quite surprising to see how different it is socially. What you just said makes sense to me. But I guess the people are not my specialty.

Emma Johnstone: Tim, any…

Tim Flannery: The coal mining lobby has been so central to Australian policy to economic life for so long. And they're just so powerful and so deeply embedded. And that along with this frontier mentality that you just use what's there and move on, has led to this toxic mix. But you know, the way to defuse it, I really think is respectful listening. I mean, I've probably spoken to 10s of 1000s of Australians in groups about climate change. And you know, the bloke who stands up and starts screaming at you and said, it's just a load of rubbish. I don't put him down, it's his peers in the audience who just say, that's disrespectful, you know. And so having a respectful dialogue with people, so they know they're being heard, is really, really important.

Emma Johnstone: So that's, that's the one on one conversations, but countering that, the general media platform, which is what we're talking about here as well, are the strongest arguments now perhaps the economic arguments that it actually makes powerful economic sense, and good sense for jobs and wellbeing, to enact really rapid carbon emissions reductions, and we have the technology and we have, you know, the insurance predictions that everything will be problematic if we don't do it, are they the best arguments to make now?

Tim Flannery: Look, it is true that we've got the tools we need, we know that, but the transformation of the electricity system alone in Australia is a complex job. And, government needs to take it deadly seriously, and set those targets to say, we want to have this, just we're not burning fossil fuels, five years, or 10 years from now, if we did that we could do it, it would cost and it would be a complicated job, but we can do it. When you get on to industrial heat and processes. That's another really big job. It's not easy. I don't want to pretend it's easy, and it's not going to be cost free. But we know we need to do it. So it's setting those targets. And I think what you're saying about the parliament is absolutely right, they’re the people that need to set those targets and objectives for us, then we can unleash our creativity, their finances to do that job.

Rebecca Huntley: Yeah, I mean, even even the most, you know, ambitious people in the private sphere, whether they be investors or whether they be captains of industry, so there's only so many levers we can push, unless there is consistent policy, certainty, around climate and a real agreement from state, and particularly the federal government, you know, we can't, there's only so much we can do. There's a lot they can do. But that policy setting and that government leadership, is absolutely critical, at every level of government.

Emma Johnston: And even if we do get those really detailed plans and those commitments, we are actually still going to need a lot of STEM trained professionals, particularly in data science and material science, in chemical science and physical sciences, to solve some of those nuttier problems that we know we have to face when we transition big energy systems.

Rebecca Huntley: Which means we need the federal government to effectively fund universities of all kinds, and research, to be able to provide those kinds of solutions.

Emma Johnston: Absolutely. So universities are facing a financial crisis at the moment, and it will impact our capacity to provide that research program. So along with investment in societal transformation, we are going to need substantial targeted investment in these areas, and particularly, some of them are STEM areas. We've got another question I'll go to as well, which is, it's a personal one, what can we do in our everyday lives that will have the most impact reducing climate change? And how can we set an example for others to follow? So I want to focus on the second part of that question, which is really around, does setting an example effectively communicate climate change? Does it affect change?

Tim Flannery: Wow, this is the most commonly asked question.

Emma Johnston: Is it?

Tim Flannery: It's the most commonly asked question and the most difficult question for me in a way, because I want people to do things in their personal lives that will make a difference. But you know, the fossil fuel industry is never happier than when the spotlight drifts from it on to something else. So when the spotlight drifts on to what can I do, you know, the fossil fuel industry is off the hook. So, in some ways, it's really important to develop a sense of community leadership. You know, join a group, get involved politically, do something where you can amplify your voice, along with other people. But let's not pretend that the solutions are all with just individual action, meaning that the problem we're in is being created by the fossil fuel industry. And that's where we need to absolutely focus relentlessly, as you said, stage four lockdown to get those emissions down.

Emma Johnston: Interesting, because a lot of individual behaviour has changed as a result of COVID. But we haven't seen humongous reductions in carbon emissions. So, you know, virtually no one's driving around or, you know, a lot of reduction of activity, but carbon emissions dropping substantially for about a month in April, globally, but still bouncing back up relatively quickly.

Rebecca Huntley: I mean, one of the things I explored in the book, I look at various different emotions in the book, and I looked at this notion of guilt and shame. And that's one of the, one of the understandable, you know, tax that the environment movement took around climate was around individual behaviour, right? And this is not to say that individuals behaving collectively in the same way doesn't have an impact. But it also means that what it does is reduce the kind of solution to climate change, which is such a complex and big issue, to whether or not I decide to drive to work today. And if you say to somebody, to a woman with three kids, and it's raining, no, no, you've got a cycle, you can take your three kids to school on a bicycle, it's just too much. And what it does is, it kind of puts the impetus on the individual, and it does actually lead to this kind of sense of guilt, shame, and these are not these are not productive. And you're right fossil, the fossil fuel industry is going great, everybody's worried about taking keeper cups to work. And you know, whether or not they recycle. So there are political and systemic issues that are mostly at stake here. So if I would say to, I think, I can't remember who asked the question, is it Sandra?

Emma Johnston: Sandra.

Rebecca Huntley: The first thing you've got to do is vote, and you've got to vote with climate as a major issue and tell parliamentarians, get them scared, that that's why you're voting. You can do things through, you know, through your superannuation and your investments, and through what you do with where you decide to invest your money. But really collective action, political action, and systemic change is what it's going to take. And as much as individual action is important. I don't want people to think that climate change is something just for them to solve, through what they do in their home environment. It's not going to be the main way that we're going to do this.

Emma Johnston: What about the positive aspect, though, of creating social norms that are cognisant of environment, as an important thing, as a real thing that can be exhausted. Adriana?

Adriana Vergés: I mean, what I was going to say about this, I mean, I fully agree, that is obviously not an individual action that is going to change, that is going to really improve things. However, I don't know if you've seen this show on the ABC, it's called Fight for Planet A. Craig Lucas was the presenter, and I heard him talk about this the other day, because he also presented a show on the war on waste. So, and he saw a lot of, well, there was a lot of behaviour change that resulted from this TV show. And what he was saying is that, you know, maybe the change doesn't come from the top down. It's like, all these individual actions are what's going to create the change that needs to happen at the top, you know, so it's not that you know, me eating less meat is gonna really be that, you know, make that difference, but it's actually all of us putting pressure on our, you know, elected members

Rebecca Huntley: If we can agree that the problem is so pressing, that we need to throw everything at it. I'm not saying to people don't stop being a pescatarian or don't stop cycling. But I'm saying that if we continue to make the pathway to solving climate change about what can I do as an individual, then that's the problem.

Emma Johnston: So it can't be solely about that. Tim?

Tim Flannery: I just wanted to tell you a little story. You know, a few years ago, I was up in coal country in Queensland, giving a talk on climate change, and it was an audience of 100 people, big bloke there, you know, could see the coal on his skin, you know, we gave the 15 minute talk and first hand up was his. Great big muscley bloke stood up, and we thought, oh, we're in for it now, you know. But he said to me, look, thank you for your presentation. He said, I used to be a farmer. And I can see the climate change helped lead to my bankruptcy at my farm. He said, I’ve got two young daughters, I needed a job. So I took a job in a coal mine, you see, can you tell me am I doing the right thing? It just about broke my heart, you know, but there's a man stuck in an economic paradigm where he has no choice. And this is what, we talk about doing the right thing. But unless we can change that paradigm, we're not going to get anywhere. And we need to treat everyone with respect. Everyone, from the coal miners through to the sceptics and others. Just understand that unless we change our bigger view, we're not going to succeed.

Emma Johnston: And it's for the younger people that we are trying to succeed. It's for the people who are going to be around dealing with climate change for a lot longer than anyone on this panel. So we have some pre-recorded questions from primary school students. And I'd like to throw if I can to one of those pre-recorded questions, and we'll see if anyone on the panel can answer it.

Pre-Recorded Question: Hi, I'm Hannah and I go to Alexandria Park Community School. My question is, how can communities use practical and affordable techniques to carbon sequester and combat climate change?

Emma Johnston: Great question. So Tim, I'll throw that one to you.

Tim Flannery: Hannah. That's a great question, I spent years trying to answer it, myself. What's so wonderful about it is that we have got some very practical ways of doing that Hannah. I mean, if you plant a tree and watch it grow, you can basically see the amount of carbon that it's drawing out of the atmosphere to build its tissues, because trees are really, kind of, congealed carbon dioxide. That's kind of what they end up being. So that's one way we can do it. We can plant trees, we can look after our vegetation. But there's so many other ways, as well. We can plant seaweed, and that helps do the same thing. We can use rocks. And there's a recent study showing that if we just took all of the shavings off rocks from around the world and put them on agricultural fields, they would draw down about two gigatons of Co2 out of the atmosphere every year. We can use biochar. Biochar is a great material, you can take a plant, any crop waste, turn it into mineral charcoal, and that then sequesters carbon in the soil for a very long period of time. So as a community, planting a tree is a great way of doing it. But as industries, or as a country, we can do a hell of a lot better.

Emma Johnston: That's a great answer. Adriana, do tell us, I know you plant seaweeds yourself. So what are you doing there?

Adriana Vergés: Yeah, yeah, so we were planting these species called crayweed, this is a t-shirt of my project. And we actually work with schools a lot. So we invite schools to either sponsor a forest or you know, get involved in learning more about the importance of seaweeds. And I mean, I guess, you know, they're photosynthetic organisms, they take carbon out of the atmosphere, just like trees do. And they can store it by, you know, all the seaweed, right, that ends up in the deep ocean. A lot of that carbon then gets, you know, essentially sequestered for 1000s of years. And seagrass meadows are even more important in that respect. So, you know, they're a lot more effective at sequestering carbon than even terrestrial forests. So looking after our marine environments, and potentially getting involved in hands-on restoration is definitely something local people in Sydney can do.

Emma Johnston: And many people are getting involved in, in restoration projects or volunteerism, or citizen science. There's all sorts of names for people getting engaged in their local environments and actively restoring them. Do we know if that's a mechanism by which people's minds and hearts are changed or their understanding of the world and climate is changed?

Adriana Vergés: My understanding is that yes, I mean, you probably can speak to this a lot more, but I think, you know, things that connect people with nature help you motivate you to take action to protect it.

Rebecca Huntley: No, absolutely. And I think what so many studies have shown which looks at things like, whether that be, community solar, or some kind of, you know, you know, environmental restoration project is that if different stakeholders in the community come together to do that, and perhaps motivated by different things, that there's a sense of ownership and connection, right? And the other thing that is really fascinating too, is the extent to which that kind of that kind of activity, especially that interaction with the local environment, and an education about what climate change might be doing to that, can really shift people who are previously very kind of quite resistant to the climate message. But it has to be local. right? There's only so much that seeing a polar bear on a melting ice cap, if you're, if you're living in rural Queensland, or if you're living, you know, somewhere in Africa, is really going to connect with you. So that kind of, that personal interaction, the education that comes with that, and that sense of connection to your day to day life is critical for changing attitudes.

Emma Johnston: So we have another question, a related question from the audience. And this is, along with engaging with emotions, do we need to recognise that humans resist bad news at a deep psychological level? Do we need to be more strategic? So this is again about how to change minds?

Rebecca Huntley: Yeah, I mean, look, I've dealt, I've struggled with this a lot. And I went into the book with that kind of, that very, kind of, statement that you've always got to be positive, right? And the problem with that, I'm not saying that – there has to be a role for hope and optimism – is that unless we get a sense of what can be lost, what has already been lost and what's at risk, then we are not going to motivate people, right? Now, do we have to endlessly tell people about a, kind of, apocalyptic future that's around the corner where it'll all be, you know, everything we love will be destroyed? No, that's not motivating. But, people will engage with darkness and challenge if you give them some solutions, and you give them some power to deal with it. And so I think it has to be a real balance of light and dark, loss and gain in talking to all kinds of communities from wherever they are on the spectrum of climate change, about what needs to happen.

Emma Johnston: I felt that we were getting to that point at the end of the bushfire season, this year, that catastrophic, unprecedented bushfire season where we lost so much of our native vegetation, so many houses, I felt like we were getting to that point of a tipping point in public opinion, but it seems to have disappeared.

Tim Flannery: I'm not sure about that Emma. I think that that feeling is still there. You know, I remember back last summer, the months of just unbreathable air, and the issue people had with that, and the hundreds of people who died from that. And you know, if you go out into the south coast of New South Wales now, you'll see there's communities that have still been catastrophically impacted and will be for years. Those homes won't be built, rebuilt for years, much less the businesses and the thriving communities that were there. So that's a lived experience for many Australians, you know. Sure, COVID, has come along and is now, and it's dominating the news cycle, I mean, there's no doubt about that, and dominating a lot of people's thinking. But I do think that that drumbeat of climate change is still there. And once we have breathing space to think about it, again, we can, I think, it will just rise, to be honest.

Emma Johnston: Rebecca?

Rebecca Huntley: Oh, I’ll tell you one of the things that the research I'm doing on attitudes to COVID shows is a renewed sense of the importance of outdoor space, whether you live in… wherever you live. Can you imagine the air quality of the fires overlapped with overlapping lockdown? It's almost unbearable. So we need to take the fact that communities of all kinds have recognised that a walk in the park, taking the dog out, at a time of lockdown is more important for mental and physical health ever before, as a springboard for renewed recognition of the importance of protecting those environments, that outdoor space wherever it is. And I think that's the real opportunity now.

Emma Johnston: And those beautiful blue skies that we're getting, what a contrast to a summer that was grey and dusky. So there's a question here, there's a discourse on what really triggered climate change. Economic growth is often considered as a major aggravating factor. Is this a misleading statement? And does it matter? I might, might say more broadly, does it matter if we understand or not, what's triggering climate change? Anyone?

Tim Flannery: Look, of course it matters, it absolutely matters. I mean, And, you know, unless we know that a virus is causing the pandemic, we're helpless to act, you know? We know what's causing climate change is the burning of fossil fuels, you know? And the fact that until recently, fossil fuels have been the, kind of, the engine room of our economy.

Emma Johnston: So it is an economic trigger.

Tim Flannery: But now that's changed, that is decoupled, the cheapest form of electricity generation over much of the world now, is wind and solar. So we know that with a clean power house, we can build a whole new clean economy and start solving the problem. But we have to recognize what the problem is, its fossil fuels and the burning of fossil fuels that's caused the problem.

Emma Johnston: And now economic inertia. So Adriana?

Adriana Vergés: Yeah, well, I think the big difference between the COVID challenge and climate change is yes, that we actually do know what causes climate change. And we know how to get out of here. We know, you know, we actually have the science that can get us out of here. We obviously still don’t with COVID. So yeah, that's the big difference.

Emma Johnston: That actually makes me feel somewhat better. Let's go to another question, from a, a pre-recorded question, from a primary school student. And this one, I've got to warn you, it's very, it's futuristic, it's gonna get you right into the future, this one.

Pre-Recorded Question: I'm Elijah from Alex Park. And my question is, which creature will reign supreme after the human race dies off?

Emma Johnston: It's a bit bleak.

Rebecca Huntley: Well I think it's Kardashians.

Emma Johnston: Kardashians!

Rebecca Huntley: Yeah, that's my non-scientific touch contribution there.

Emma Johnston: I think all humans were knocked off. That's a great one. What about you, Adriana?

Adriana Vergés: I mean, I think without a doubt, there's winners and losers, right? So nature will keep evolving. And it seems like the biggest losers here are us, you know, we are self-destructing, if we continue the trajectory that we're going on. So humans will disappear. Who will win? I mean, I reckon definitely, bacteria will be part of the winners. But I'm sure there's other creatures, like in the marine environment, yes, jellyfish tend to dominate when things get really bad. But I know what you think, Tim?

Tim Flannery: Well, you know, I don't think we're in control, at the moment. We're just, we're just a little pimple on a great big mound of metabolic activity.

Emma Johnston: That’s gross.

Tim Flannery: The thing that's always on the planet has created the atmosphere in everything and the bacteria, they will be here after we go, they will continue to be in control. So, yeah.

Emma Johnston: Okay, I hope that answers your question that the world will be full of microbes and a great diversity of them. Kind of question which somewhat relates to that a little bit, it's triggered by that, perhaps, how we deal with climate anxiety? I mean, if people are really, and young people are really thinking, what happens when all humans die off? There must be a huge amount of anxiety that accompanies those thoughts. How do we help people manage that anxiety and keep working through the problem?

Rebecca Huntley: So you're right, so most… a lot of medical, mental health professionals and associations from around the world have developed some really effective guides and, and support groups for people dealing with climate anxiety. But a lot of the studies show that the best antidote to climate anxiety is action, collective action, so trying to find a group of like minded people that have decided just to try and do something. And that doesn't mean that you don't have anxious moments, or moments of anger, or moments of frustration, but they're shared, and they're channelled into a goal. So for me, my climate, climate anxiety is, is offset by work on climate change. But the other thing, I think one of the other things, because this question gets asked a lot in combination with what can I do, to do something about climate change. And I often say, Look, you don't have to suddenly become somebody different, or do something different. It kind of doesn't matter what you do. There is a climate angle, so take your thoughts about climate change, it doesn't matter if you're an accountant, it doesn't matter if you're pharmacist, it doesn't matter if you have a job or not. There is some way to bring action on climate and the environment and fold that into the life that you already live. And if you have anxiety, that means that… I mean, the last thing we need is a whole lot more meetings to go. You can find a way to kind of put a climate lens over the world that you already live in.

Emma Johnston: Everyone needs another Zoom meeting, I'm sure. So look, Christiana Figueres, was here in March talking about The Future We Choose. So that's a book that she has co-written. I highly recommend it. But one of her key strategies in the book is stubborn optimism because as she says, have you ever heard of anything that was achieved that started with defeatism? So this does relate to how we psychologically deal with the drama of climate change. So I wanted to close this wonderful discussion, to give you each a bit of time to tell us how you find optimism and what gives you hope. And I'm gonna start with Tim here.

Tim Flannery: Well, you know, I, look, Christiana is one of those great heroes of climate science. I've worked with her, known her, for a long time. And in that book, she made an incredibly important point that gives me optimism, which is that for most of her career, in the international negotiations, it's been a win-lose set of circumstances. So someone would win, someone would lose, that was going to go nowhere. She said we're now in a world of win-win possibilities. And that's because the clean energy sources have come down in price so much. So we can have development, we can have effluence, based on clean energy, a better way of doing things. It's a win-win. So that, to me, is my sense of optimism. There's that, but there's also these wonderful young people you meet, who say, the electricity system, I can fix that, I'm here to do it, they might not know entirely, but I reckon now give it a red hot go, you know? So that energy that young people bring to this whole debate where they sweep away the cobwebs and old thinking, and just say, nup, we're going to fix this, you know? And that is tremendous. And, you know, they're my two sources of optimism beyond that, source of sanity, is really my family and doing a few things that, that give me a sense of achievement, you know, so it might be just putting some native plants in, you know, instead of weeds, might be helping people, but whatever it is, it's something that gives you an immediate sense, because when you work in the climate area, it's such a long game, you need you need some jollies, as I call them, on the way.

Emma Johnston: Well knuckling down and finishing that next book of yours, that will give you a sense of satisfaction. Adriana, where does your hope come from?

Adriana Vergés: I think, yeah, without a doubt, it comes from nature. It comes from spending time in nature and, and helping people connect with nature, in general, as part of my job. And whenever I do that, I can see it really works, you know? And I can see there's a growth of citizen science, kind of, interest, for example, that demonstrates how, you know, people are really thirsty for a stronger, deeper connection. I think, with that comes, it just follows that you'll want to protect it. And so, yeah, nature.

Emma Johnston: So, is it also the science of working on solutions to problems? Is that part of where?

Adriana Vergés: Absolutely. Yeah absolutely.

Emma Johnston: Do you notice other scientists moving into that space, away from describing the disaster to working on solutions and interventions?

Adriana Vergés: I think that's right, yeah, I think for a very long time, you know, scientists just became really, really good, at documenting better, and better and better, you know, all this horrible degradation, I think there's definitely, I'm seeing a very strong shift towards trying to, to fix those problems, and, you know, stop with the documenting of the decline. And, and that's, that's going to be a part of the solution.

Emma Johnston: Wonderful. And, Rebecca, your thoughts?

Rebecca Huntley: I feel that I have a kind of moral and ethical obligation to be optimistic, because I have three children. I don't think I could say to them oh, look, it was all too difficult. I'm going to build a bunker, and we'll just stock up on canned goods. I, so I can't, I have, I have to be optimistic, because I brought them into the world, and I want them to grow up in a livable world. So I look for sources of what I talk in the book about, resolute hope or sceptical optimism, which is not to say, Oh, it'll be fine, and we'll just invent something, and it'll all work out. I mean, a hope and an optimism that's based on an understanding of the challenges that we already face in the ones ahead. But, you know, having spent 15 years thinking about encountering humans in all of their complexity, I generally think that we're up to the challenge, if we've got the right leadership. And then, what I also do, what I also find really hopeful and optimistic is when I meet people who are unlikely converts to the climate cause, so they don't look like environmentalists, but suddenly, something clicked in them. And they're doing something extraordinary, in climate change. So they might be somebody who's been working in the fossil fuel industry for 20 years, and suddenly they're like, I can't do this anymore. They used to be a coal miner or they used to be a farmer that came from four generations of National Party voters, and suddenly they're a passionate environmentalist. And I even think about it in terms of myself, if you'd said three years ago that climate change would be my thing, and the thing I'd focus on, I think, no way I like to wear high heels, I'm not interested in composting, but it did, it worked for me. And I think it can kind of work for everybody. So I'm optimistic when I encounter people who are on that journey, and like I said, I have a moral responsibility, moral, ethical responsibility, obligation, to be optimistic as a mother, and as somebody who loves this country and loves this community and wants to make sure that we don't have rolling, horrible bushfires for the rest of my children's life.

Emma Johnston: Wonderful story, that stubborn optimism is obvious in all three of you. I tell you, I get a lot of hope and optimism from working with scientists, actually. Because when you have a vast array of them, they're all working on something really exciting. They're all at the cutting edge of discovery. And many of them are turning to climate challenges, because they're seeing it as the number one problem for the globe. And they're saying, what can I do? And because they work in these diverse fields, they could be developing new ways of transmitting electricity, that's just that little bit more efficient. Or they could be working on how to recycle materials so that we, you know, suddenly don't need to make a huge theatre out of new stuff, and new plastics, and new products, we can recycle them. There's all sorts of work going on. That gives me a huge amount of hope. The other thing that gives me hope is that in the past, we've gathered together and we've agreed to make compromises to change products, to change economics, in order to save ourselves. And I think Adriana, that brings us back to one of the stories you began with, of the development of the Environmental Protection Authority, not just in Australia, but right the way around the world, that massively improved water quality in many, many nations to the point where there's even aspirational swimming right up at the very top of estuaries. So it's a positive note to end on. I want to thank Tim Flannery, Adriana Vergés and Rebecca Huntley very much for your contributions this evening. I want to thank everyone who put a question in this evening. No, I didn't get to all of them, but I had to make space for those primary school questions as well. So thank you for tuning in to We Still Need to Talk About Climate Change. And to hear more about our events. Please subscribe to the UNSW Centre for Ideas newsletter, and I wish you all a very good night.

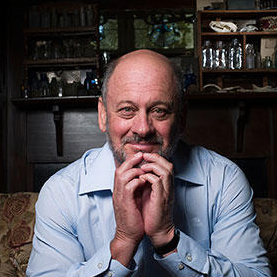

Tim Flannery

Tim Flannery was Australian of the Year 2007, and Australia's Climate Commissioner 2011-2013. He is Chief Councillor and co-founder of the Climate Council. He has published over 30 books, including ecological histories of Europe, Australia and North America, and has discovered and named 30 species of living mammals mostly from Melanesia.

Adriana Vergés

Adriana Vergés is a marine ecologist and conservationist in the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences at UNSW Sydney. Vergés' research focuses on the ecological impacts of climate change and the conservation of the world’s algal forests and seagrass meadows. Much of her research takes place underwater. Vergés is passionate about communicating science to the wider public, especially through films, art and new media.

Rebecca Huntley

Rebecca Huntley is one of Australia's most experienced social researchers and former director of The Mind and Mood Report, the longest running measure of the nation's attitudes and trends. She holds degrees in law and film studies and a PhD in gender studies, and is a mum to three young children. It was realising she is part of the problem older generation that caused her change of heart and to dedicate herself to researching our attitudes to climate change. She is a member of Al Gore's Climate Reality Corps, carries out social research for NGOs such as The Wilderness Society and WWF, and writes and presents for the ABC.

Emma Johnston

Professor Emma Johnston AO is a marine scientist at UNSW Sydney and a national advocate for improved environmental management and conservation. Emma studies human impacts in the oceans including pervasive threats such as climate change, plastic pollution, and invasive species. Emma conducts her research in diverse marine environments from the Great Barrier Reef to icy Antarctica and provides management recommendations to industry and government. In recognition of her contributions to environmental science, communications, and management, Emma has received numerous awards including the Australian Academy of Science’s Nancy Millis Medal, the Royal Society of New South Wales Clark Medal, the Eureka prize for Science Communication, and in 2018 she was made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO). She is immediate past President of Science & Technology Australia, a current Board Member of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and Co-Chief Author of the Australian Government’s State of Environment Report 2021. Emma is a high-profile science communicator and television presenter for the ongoing BBC/Foxtel series, Coast Australia and has appeared multiple times on ABC Catalyst, The Drum and Q&A. Emma is currently Dean of Science and Professor of Marine Ecology and Ecotoxicology at UNSW Sydney.