The Price of COVID

While many of us (sorry Melbourne) spent 2020 believing we had escaped the worst of the pandemic, 2021 brought forth the ugly reality of living with the virus. Even as the nation returns to something that feels like normal, beneath the thrill of gigs, gatherings and barista coffee, it’s clear the pandemic has changed the picture for good.

We’ve seen our governments and fellow citizens succeed at some things, fail badly at others, and discovered who ‘essential’ workers really are. After two years of arguing about how to ‘balance’ public health and the economy, what have we actually learned?

Chaired by author and broadcaster Benjamin Law and featuring economist Richard Holden and business leader and CEO Sam Mostyn, this talk explores how the last two years have challenged our health systems, and shown us what went missing as we globalised our economy.

What will happen as fortress Australia wakes up from the COVID spell?

The Reckoning is presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and Sydney Festival. UNSW Sydney is the Education Partner of the 2022 Sydney Festival.

Transcript

Benjamin Law: Welcome to The Reckoning, a series of talks co-presented by Sydney Festival and the UNSW Centre for Ideas. On Benjamin Law, and the conversation you're about to hear, The Price of COVID, features myself, economist Richard Holden, business leader, Sam Mostyn. We hope you enjoy the conversation.

G'day everyone, and welcome to the UNSW Centre for Ideas, albeit, online today. And today's session for the Sydney Festival, The Reckoning, The Price of COVID. My name’s Benjamin Law, and I'm really honoured to be joining you here. Well, when it comes to my case, at least, on Gadigal country, part of the great Eora nation. First Nations People on this continent have been sharing knowledge and stories here for tens of thousands of years, and together they constitute the oldest continuing human civilisation the planet's ever seen, and I'm grateful to Elders past and present, that we can continue sharing stories and knowledge here on what is and what will always be Aboriginal land. Now, COVID is not going away anytime soon. It's, of course, the reason we're having this session online in the first place. And I don't think it's a stretch to say that there isn't a single person on the planet whose life hasn't been affected or irrevocably changed by the virus. And that the world's in a state of I think, collective grief, over people that we've lost loved ones and milestones that we've missed, and the lives that we used to have. And although now we're officially living with COVID, I think it's time to take stock and ask what's been, and what will continue to be, the cost of all this. And we're talking about cost in every sense of that word, financial, political, economical, the cost to our physical and mental health and our healthcare systems, the everyday cost of broken supply chains, the specific cost to young people and their sense of the future, the specific costs to senior Australians and their sense of safety and care, the cost to our social fabric, the trust in our institutions and our sense of community. We've had two years of arguing about how to balance public health and the economy. So I think maybe it's time to start talking about things we've learned. We've seen our governments and fellow citizens succeed at some things and do pretty badly at others. We've discovered who essential workers really are. We've been angry, we've been smug, and we've been frustrated. And all of this would also be naive to start talking about things we might have gained, things that we've learned. Well, I'm going to dive into all of that and more with our two brilliant and overqualified guests today. Our first guest is a Non Executive Director and Sustainability Advisor, renowned for her governance roles across business, sport, the arts, policy, diversity, Indigenous and women's affairs and the not for profit sectors. She's the chair of ANROWS, Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety Limited, also chairs the Australian Women's Donors Network and is president of Chief Executive Women. She was the first woman appointed to the AFL commission and advocate for the creation of the AFL Women's League, was the 2018 AFL W Cup Ambassador, has been a chair of Sydney Australia Carriageworks, and a non executive director at many, many more. And for all this work and more, she was also awarded an AO in the Australia Day honours last year, g’day Sam Mostyn.

Sam Mostyn: Hello, Ben, lovely to be joining you here on Gadigal land as well. I'm here in Sydney on Gadigal land. And I'd like to join you in paying respects to Elders, and thanking those Elders and communities around the country for their enduring support for, not just the storytelling that we're doing, but also the protection and the preferencing of health and community that we've learned a lot about through this COVID. Wonderful to join you.

Benjamin Law: Thank you so much, Sam, we're so thrilled that you can be here today. Our second guest is a professor of Economics at UNSW business school, Director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub, at UNSW Business, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative and president of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. He's also been on the faculty at the University of Chicago, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and received an AM and PhD in economics from Harvard University. And he's written on a lot of things like network capital, political districting, the boundary of the firm, incentives in organisations, mechanism design, voting rules and blockchain. And you might have raised work in places like the Australian Financial Review, The Australian, The New York Times, The New Republic, the Sydney Morning Herald or his regular column in The Conversation. G’day Richard Holden.

Richard Holden: G’day Ben, great to be with you. And I'm coming from Darkinjung land today. Great to be here.

Benjamin Law: Thanks so much, Richard, we're stoked you could join us. Hey, where do we even begin with this conversation, you two? Because it's a huge topic. But I thought we might want to start with a bit of a recap, and comparing expectations versus reality, because we have been facing some hard realities over the past two years. And Sam, I might start with you. Let's cast our minds back. I know that time is as elastic as our clothing nowadays. But look, in April 2020, this is the first wave of COVID, hitting Australia firmly, and I remember that because my sister was giving birth around that time, so it's very, very stuck in my mind. You co wrote with Travis McLeod for The Guardian at the time, we now have a chance to mobilise the nation around the COVID-19 missions and moonshots that help us deal with this crisis and prepare for the future. Now, we're going to get into the specifics soon. But I was wondering on a big picture level, can you reflect on your expectations and hopes, then, when you were writing that, versus what the reality feels like now?

Sam Mostyn: Thanks, Ben. You're right, and we do live in liminal time, so it's elastic, and we kind of don't know what is long and short anymore, and it's difficult to think about back then, because so much has happened. And so I think at the time we wrote that piece, we were inspired by another economist, Mariana Mazzucato, who had visited Australia a few years earlier, who had talked about this notion that governments, in collaboration with many other parts of society can set great missions, but they need to be the kind of missions that can encourage a population and actually do the heavy lifting on things that really matter for our future. And so we used the mission concept to say, Australia could do that, and actually must do that at the time, because we were inspired by the fact that our governments had actually shown at that point, that they could do things rapidly, do really big things rapidly, close the border, the national border, make big payment systems changes that were inconceivable before COVID. JobKeep a JobSeeker, they were big, big payments to actually keep people attached to their work. There was a sense that government could come together nationally, so the federal and state relationships that were being exercised at that time. So Trav and I thought at the time, if governments can do this in this crisis now, and the population that actually is being very compliant with rules, we're not as larrykin as we like to think sometimes, we were complying, we were staying at home, we were distancing, if we could pull that together, surely, there was a big mission that governments could work with, in collaboration with other parts of our society, to actually see ourselves through, and not let ourselves fall into the trap of saying, we're going back to where we had been, before this crisis, that we could actually design and create a series of missions around an economy and a society that would then value those things that we had learned about through the early stages of COVID. So we had enthusiasm, we had optimism, and we had plenty of proof at the time, that governments could actually do things we'd never imagined, and do it in our interests, and do it in the long term interests. And were actually at that point, preferring our health and wellbeing over the ordinary discussions of the economy that we've got quite used to, the idea of deficits and getting back in black, all that kind of stuff evaporated when the country was in crisis, from a health perspective. I have to say and we'll pick it up later in the conversation, I'm sure Richard has much to add to this, I've lost that optimism and enthusiasm, because despite many, many people right across the country, putting up those kinds of mission ideas, and having great confidence about the need for long term planning, and to learn, as you said, from what we've done badly, and turn those into the opportunities to change. We're seeing at the moment, a lot of short termism, a lot of reversion and a lot of missed opportunities. And if anything, we've realised that some of the fragility that was in our system, as you entered to COVID, is now fully exposed, and we must deal with that. And I think as a population, we've all felt that, along with that grief, I think at the moment, many are feeling a sense of abandonment and the confusion about the role of government in protecting us now as we come through this third wave. So yeah, I'm less optimistic, but it's conversations like this that are vital to actually encourage the population, I think, to really say we need long term vision, and not going backwards, but set a whole new economy and society around the things we've learned.

Benjamin Law: Thanks Sam. And we will talk about the missions, the specifics of those, what they were, and maybe how far we've fallen short, soon. But also thank you for reminding us that in amongst all of the fear of that first wave, that there was a sense of optimism that the federal government that our institutions weren't as lumbering as we thought they were, and maybe we can talk about why that idea has receded over time. Richard, I want to flip over to you now, because I want to go back to June 2021, so this was the middle of last year. And this I think, was really during our Delta lockdown, our big second wave of lockdowns that we experienced, especially here in Sydney, and of course in Victoria as well. And you said, in the fin review, I believe we're going to have to tolerate some nonzero COVID-19 in the community, that reality was becoming more and more clear to us. And we were having to confront that as opposed to our first wave, what living with the virus would look like on the other side. I'm curious, what did you foresee happening in an ideal version of that scenario, which was tolerating some nonzero COVID-19 in the community, and how do you see it actually having panned out?

Richard Holden: Yeah, I think it's a great question. I think what I, what I thought at the time was, we had got to the point of getting many things done right, we locked down the international border back in March of 2020, we'd stood up a contract testing and tracing regime, we've come to understand a lot more about the virus. And at that point, myself, and basically every other mainstream economist in the country said, you know, we've got to stop talking about trade offs between the economy and public health, you can't have a functioning economy with an out of control pandemic, the best way you can take care of both public health and the economy, is to shut things down for a period of time and get those public health measures in place. Now, over time, you know, that had been done, we've been very comparatively successful, we look around the world, and we'd got access, finally, to vaccines. And I'm sure we'll talk more about the vaccine rollout. But by the middle of last year, we're in a situation where we can see on the horizon, being in a situation where we had a very high proportion of Australians vaccinated, we understood a lot more about the virus, we understood what preventive and precautionary measures could do. And we're in a position going forward where we should do all the low cost things, maybe wear masks on public transport for the foreseeable future, maybe forevermore, there's just not a particularly high cost thing to do. But we can be in a position to safeguard our public health and the economy by doing the relatively low cost things, but not thinking we could have zero COVID forevermore, but it's worth emphasising that back in early 2022, this idea of a trade off between public health and the economy was something that, as I say, I and basically every other economist said was a false dichotomy. What we needed to do at that point for both public health and the economy, was to make sure that we took care of the pandemic. But as you go through these things, and over time, you need to adapt to changing circumstances and circumstances are very different, when we have a number of very high efficacy vaccines, we know more about things, the strains of the virus have changed, and we and our leaders need to adapt to those changing circumstances.

Benjamin Law: Richard you talked about that false dichotomy of the economy versus public health. And I think that that story was very prevalent for the last two years, like, if you pull this lever, the other one will suffer, pull this lever, the other one will suffer? Do you think Omicron has changed that narrative given that now, the virus is well and truly within our community, and our economy has taken such significant hits?

Richard Holden: I actually actually think it's reinforced it. So there was some great evidence from two University of Chicago economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson, and that came out late in 2020. And what they looked at is, basically, how much of the drop in economic activity in the US was due to formal lockdowns, like government mandated or government coordinated lock downs. And how much came from, what I've called the stealth lock down, people voluntarily saying, you know, it's scary out there, I don't want to get very sick, I'm going to cut back, I'm not going to the movies, I’m not going shopping in person, I'm not going to restaurants and bars and so on, even if I'm allowed to, and what they're able to do, because there's lots of places in the US that are basically one… cities that have sort of one economy, but are in two counties or two states. Think of it as like a couple of hundred Coolangatta, Tweed Heads. They’re able to actually have a kind of natural experiment where they said, okay, what proportion of the drop in economic activity in the US was due to the self lockdown and was due to the government mandated lockdown. And it turns out that high 80%, about 87, 88% of the drop in economic activity is due to the self lock down. And that's exactly, in my view, what we're seeing now with Omicron. I think it's the first time it sort of really, come to the fore in Australia, we say, hang on, there's no formal lockdown, but businesses are reporting massive drops in economic activity. Consumer confidence is at its lowest level since 1992. How can that be? Because there's a lot of virus running around in the economy, people don't want to go out, even if they're allowed to, and people aren't very confident about things, and they look at mixed messages from governments, they looked at mishandling of things, and they say, I haven't got a lot of reason to feel super confident right now. And you know, the biggest enemy of people spending money in economy, businesses investing, employing people, planning for the future, taking on new goals, new projects, opening up new lines of business, is confidence. And so I think we're seeing right now that again, we're always going to live with a situation where even if there's going to be some virus in the community, you can't have it be out of control, and think that you're going to have a well functioning economy.

Benjamin Law: You know, Sam, if these two things are inextricably linked, economics and public health, and especially now, we see that so clearly, I want to go back to something that you wrote in 2020. And you used a Wizard of Oz analogy, and you're speaking to my gay heart, when you use something like that. But you talked about what happened in aged care in Australia, lacked heart that using, say, private contractors with quarantine lacked brain, and we all saw how that panned out. But I really want to focus on the last thing you pointed out, that the Australian economy and society risks becoming the Cowardly Lion, with how it's moving. What do you mean by that? What's the element of cowardice in all of this?

Sam Mostyn: We worked very hard to think about the right analogy at that time. And we came up with the Wizard of Oz, and we're in Oz, and, and there was a man behind the whole thing, pulling the levers. And we kept thinking, you know, there is a strong analogy here with what we're going through. And to that courage piece was, it had taken great courage at the beginning to do those things that Richard and I both referenced that were completely out of the box economically, and from a national policy point of view, we'd shown courage, in fact, our leaders kept telling us how lucky we were to be in this country, because of the way we were handling the pandemic and how well we were coming through it. But the courage to think about the long term, the courage to actually acknowledge what we had learned, once we're in the middle of COVID, that would take some courageous action by those who had to put aside the short term and perhaps political expediency, and put ahead, the long term for the country, the health issues for the country, and put aside any notion that it might actually affect the electoral advantages or otherwise. So I think, I was reflecting listening to Richard, what if we were having this pandemic, in a period where we had a government, a federal government that had five years to run, or four years to run, and wasn't so mindful of a an election campaign coming up, because we everything seems to be building towards, who's going to support decisions, as of May, this coming year, if you took off the kind of fear of the polls, and set back, the courage we need is to acknowledge what it is that was going wrong in our system for COVID, how that was exposed, and how to dig deep, and build a courageous mission for the country, for the long term. And for me at the centre of that, Ben, it's caught up in that health economics discussion. But we learned that we don't care about care. So we had had, as you said, the Royal Commission into aged care before this pandemic, we've had Royal Commissions into disability care, we know that care has been a big issue for this country well, before we came into COVID. Suddenly we had this clapping around the world hitting saucepans with thanks for care workers and frontline workers. But we didn't care about the workload on carers. And we didn't actually understand that up until this time, effectively, our care has been provided by underpaid or unpaid people in our community, many of them women, many of them are from very different cultural backgrounds, many of them doing it silently and without any expectation of thanks. But that's what's been holding our care system together. And we see it now at the middle of Omicron. Where the care system, the formal care system, our hospital systems, and emergency systems, are falling apart. And so what will be courageous would be to actually stand up and apologise for that and say, we're now going to preference care workers and actually put a price on this, we're going to pay, we're going to have proper workforce plans for anyone in the care sector. And by care, I don't just mean hospitals and doctors, I mean everyone on the frontline, teachers, nurses, those people who are giving us our shots, but all the way through to care, aged care, disability care. And that would be a courageous act, to actually say it and say, irrespective of the budget outcome, we're going to put this at the centre, we’re going to put care at the centre of our economy, we're going to pay for it, plan for it, honour those workers, rather than just clapping, by actually saying they need to be paid well, and we need to then deal with the gender issues and the cultural diversity issues that sit in those care systems, that I think now are holding… are our informal social safety net. They certainly are in the US, and we used to think we were much better than the US, because of our Medicare system, our public health system, but we're getting pretty close, I think, to a situation where that informal, largely women healthcare sector, is our social safety net, and we I just don't think we've complained courageously for a future without acknowledging that and putting it front and centre in the discussion about the national priorities, alongside many other things we can learn from COVID. But that one to me was the big learning that we just can't go on like this anymore.

Benjamin Law: Such a compelling argument about the need for care at the centre of our economy. And within that, Sam, what I hear is maybe an urgent need to reframe our metrics of success within an economy, as well and what we understand to be a successful economy. I mean, Richard, this is the last two years that's really thrown our understanding of value within an economy. Is it worth reassessing what we define as success? I mean, we look at the New Zealand model, they talk about the happiness index and whatever that means, different countries and nation states use different measurements and metrics of success. Should Australia be having that same conversation too? And has the pandemic, especially given us the opportunity to do that?

Richard Holden: Yeah, I think we should definitely be having that conversation now. Full disclosure, I'm not too big a fan of the, sort of, happiness budget and well being budget, I think those are somewhat amorphous concepts, is maybe the nice way to say it. But it's an important discussion to have. I think good economists have always known that there's a very important distinction between market value and social value. And just because something is highly valued in the market, doesn't mean that it has enormous social value, and vice versa. I think Sam's rightly pointing to the care economy as something that sometimes is unpaid. So in a sense, has no market value, but is incredibly socially valuable. And you know, there are lots of things that are valued in the market that cause externalities, that cause harm, like pollution and carbon emissions and so on. And I think thoughtful economists have known for over a century that to try and equate market value with social value is a big mistake. And of course, you know, philosophers like Michael Sandel who’s put that very forcefully for decades now. So I think that, you know, that discussion should be had more openly, I don't think it, sort of, requires overturning big concepts, or very huge barriers to thinking about that. But this is just a good time to have it. One thing that is focused on I think too much in Australia, and I'm a very conventional economist, so I do believe that over the long run budget deficits do matter, I don't think you can just print money willy nilly, and, you know, it's all fine to do that I'm as vocal or critical of modern monetary theory as you will find. That said, we have a very peculiar focus in Australia on balanced budgets. And I often refer to it as balanced budget fetishism. We came to a very odd position at the end of the Howard and Costello years, a good one, but a very unusual one where we had basically no government debt, certainly at the federal level. And that was a confluence of, kind of once in a generation booming economy and selling of some very large assets, the Commonwealth Bank and Telstra primarily, I think there were good things to do. I think it's good that we had no debt, but suddenly became a measure of success, as, can you have zero debt as the government, if you have any debt. If you look around the rest of the OECD, if you look back in Australian history, zero national government debt is a very peculiar situation. And I think it's hamstrung us from thinking about making, this is where maybe they'll start with dovetails with some of the things that Sam was rightly pointing out. It's hamstrung us from thinking about making smart government investments. The government can borrow long term, 25-30 years long, at around 2%. Ask yourself, what investments in the Australian community have a social return of more than 2%? And I think many of us could, you know, point to many things. And Sam and I, and many others have written about things that we could make a bigger investment in. And so I think we need to change the framing, that being a successful government, that being a successful economic manager, or steward of this country, is about having zero debt, and balanced budgets, no matter what, and I think this crisis has provided an impetus for that. And also, the reality is, you know, we're not going to have a balanced budget for the next decade. And so we should not be, you know, profligate with our spending, but we should be thoughtful about it. And we should stop worrying about a billion dollars here, and a billion dollars there.

Benjamin Law: What I'm hearing in that Richard, is kind of the dangers or the potential pitfalls of being singularly focused on anything, whether it's debt or anything else. And I wonder what other things we should be accommodating in the narrative right now. I think of the past week and Josh Frydenberg, talking about unemployment rates, how they're fallen to the lowest level since the GFC. Prime Minister Scott Morrison always wants to focus and likes to focus on the fact that Australia's had some of the lowest death rates due to COVID in the world, and both are factually true statements. I'm wondering what other considerations, facts and things should we be holding at the same time as those statements?

Richard Holden: You know, I think that the treasurer is right to point to a four point two percent unemployment as being a very good thing. And I think it's been sort of tacitly accepted by both sides of politics for far too long that something like five percent unemployment, or five and a half percent unemployment in Australia is an acceptable level and it's good enough. And I think it's good to see us aspiring to an unemployment rate that looks like three point something, not as an aberration, but as a long term thing. And I think low death rates are obviously good as well. But as you point out, it's fine to point to those things, but what else? There's obviously been a complete lack of action on addressing climate change by this country collectively for far far too long. And it need not, addressing climate change need not require hundreds of billions of dollars of government investment. There are many other ways to address it. You know, I've got my favourite plan and other people have got their favourite plan. I support the idea of a carbon dividend, putting a price on carbon and redistributing that back to all Australians equally, which is a very progressive way, belief, about three quarters of Australians [would be] better off financially. But there are also different ways to do it, and we'll find a way to do it. But I think perhaps the most pressing thing that we've put into the too hard basket for too long, by pointing to as you say, if you define success as being about one thing, then you may get that or you may get politicians redefining the facts to make it seem like we got success on that. But you know, success in running an economy, let alone a country that's a lot broader than simply an economy, requires focusing on many things and thinking broadly about what success really looks like.

Sam Mostyn: Can I throw a thought in there? Just just a couple things. On measurement, you know, I think we like to measure ourselves globally, and make ourselves, you know, talk about the comparison of Australia and the rest of the world. We spend the most in the world in educating girls and women, and we have some of the highest record numbers of women who are educated in this country. We're number one in the World Economic Forum for education of women. Last year, we fell from 12th position, about a decade ago to 70th in the world, for women's economic participation, and 50th in the world, for women's political engagement, being representatives. So just think about that as an investment. We're investing heavily in our education system, all the way up through the technical and trains and higher education. And yet we squander one of our greatest assets, women, smart women, from all backgrounds, by having all sorts of structures that prevent women participating fully in the economy. So I wouldn't be measuring our economy based on how well do we actually use the people we invest in, which takes you to what stops women in the workforce, and what leads to gross underemployment of women? So we know that one of the things we don't talk about a lot is underemployment, you know, women who can get a few hours a week around childcare, because they've chosen to have a family, things that impact women much more than men, you know, in that traditional family arrangement. So we also know that employment services has not been a strong focus. And that when you go into communities and ask those communities, how is the employment services system working, it doesn't work at community level to ensure that those that want to work can find work. So those young people, people who desperately want to work, fall out of their employment system, and certainly, that's been exacerbated by COVID. But back to women, the failure to have a proper early education and care system, which has been advocated by many economists, and many who care about our future, tells us that the failure to have universal early education means that we continue to have one in five children starting primary school with a cognitive difficulty. That's 20% of our kids. So if you think about the long term plan for the country, wanting the smartest people coming up through our education system, why wouldn't we commit an investment into our youngest children, and keep supporting them all the way through the education system and free up women and others to be in the workforce because they want to be. And so, you know, these are things we can measure our investment in early childhood, our investment in paid parental leave, that affects all communities, and allows us to use our current available workforce. And be really mindful when we talk about unemployment, that we also have to factor in underemployment and the under utilisation of some extraordinary assets we have across the country. So, I think there's such a broad range of things we can do. And I think Richard probably agrees with the notion of early education as just smart economics, in addition to smart long term care for this country, and for our children and families.

Benjamin Law: Thank you so much. It's such a significant caveat in the conversation about unemployment, which is under employment. And of course, you've written and pointed out Sam about the disproportionate jobs and hours lost during COVID, 55% of the jobs lost in one month alone were womens, and last year 60% of the job losses across Australia between June and September were jobs lost by women. You also bring up the point, Sam, about, you know where we're situated in the world, for better or for worse, and how Australia stacks up. And you sent me a piece this morning that I noted with interest, it was the Edelman Trust Barometer, which is the annual Trust and Credibility Survey that's just come out. And it involves all nations, and it shows a significant trust in democracies, generally across the board. But Australia's trust in democracies fell significantly, in this period. Our drop from where we were last year to where we are now was second only to Germany's. I mean, when we talk about the cost of COVID, I mean, this seems to be a big cost at a time where democracy around the world is, kind of, feeling the stress already. What's happened and why Australia specifically when it comes to this lack of trust in democracy?

Sam Mostyn: Thank you for referencing that. Ben. And I've been really fascinated watching the Edelman Trust Survey of the last 20 years or so. We are a country that really believes in our democracy, and until recently has been a strong, we’ve been generally very supportive of our democratic principles and institutions. And I think that's why we were so compliant at the beginning of COVID, when our big institutions told us to stay home to wear masks, and then finally, when we could get vaccinated, we did it in remarkably high numbers. So we actually are very, we believe deep in our democracy, that drop in the last few years is significant, I think, because of some stuff that Richard already mentioned. There were systems delivery failures that happened that were felt by all of us. So whether it was the failure to get the vaccination running faster and get the supplies, then backed in by the different contact tracing methods right across the country, but really, the big issue around rapid antigen testing, and Richard has written about this from very early in the pandemic, about the need to get those rapid antigen tests into the system. So that it would be, it would provide the best protective mechanism for getting people back to work and having confidence without blowing up the system through the testing we were doing. And our government failed to do something that actually we all believed that democracies and well run governments should do. And we've all been a beneficiary and felt that in some way, whether it's not going to get the tests, or, as Richard has pointed out, self isolating, and therefore causing catastrophe around the economy, because we're just not out and about because of that lack of confidence. So I think that drop is a response that says… and I think I don't think it's a permanent drop, I think it's a warning message that says, something's going to change in the delivery of things from our governments that we wanted to believe in. And if that doesn't change, I think what will be interesting electorally is the rise of the independence and community movements, who are saying, is it time for communities to take care of themselves and reject the notion of how a democracy has worked to date? You know, and so very interesting movements all over the place, which I think we can't ignore. I'm hopeful that we can reinvest in our democratic principles and institutions, and that we do get long term thinkers and a country that says that does matter to us, because it's one of our enduring strengths, our belief in our Constitution, our belief in government. And we do like government in our lives, actually, we do like the things that government provides us with, and we have traditionally, whilst also being a free market economy. So, you know, I think it's a warning signal. And it was an interesting figure that Australia ranked so highly in that drop, I think it's recoverable. And interestingly, the quid pro quo was that very marked increase, again, in Australians' belief in the private sector, and asking the private sector to behave more socially responsibly, and very strong support for the term called My Employer. So if you're with a good employer, a good big employer, that trust has risen significantly through COVID. Because people have actually felt very confident that good employers have stepped in and done a lot of things that governments weren't able to do, or didn't do, or failed to do. So really interesting data for us to consider and reflect upon.

Benjamin Law: I'm curious to hear more about the way that different demographics have felt the cost of COVID. And we've already talked about women and touched upon the very different experiences of employment, under employment, under appreciation on a basic level, when it comes to work, paid or unpaid. I'm also interested in generational differences, because I believe both of you are parents, and I'm curious, let's start with you, Richard, you know, what have your insights been into how COVID specifically affected younger people, on a big picture level, but maybe even on a personal level?

Richard Holden: I think it's it's clearly affected young people very much from my vantage point in the university sector, it's been really tough for people entering university and not being able to have what is often for them a transformational life experience in the in the first year of university, and that's gone on for a considerable period of time now, and for people graduating from university, going into the workforce, you know, one very well known economic fact is if you graduate during a recession, you take a lifetime hit, you know, people recover, but they never fully recover from that in terms of things like lifetime earnings, and we'll wait and see whether this type of economic downturn is different, you know, pandemic may be different from, if you like a run of the mill kind of recession, but we'll wait and see. But it's created an enormous amount of anxiety. And I think on the hopeful side, one of the things is we've seen how technology can help mitigate some of these things. So we've learnt better both, you know, if I think about it with my school aged children about how to do things online at school, and so on, if I think about how we've, you know, across the country got up to speed better at teaching university classes online, whether those be interactive classes, or more lecture based classes, and so on. I think there's a sort of a hopeful future for what that can mean, provided that we make sure people across the income distribution have access, you know, to the right kind of technology, the right kind of internet and things like that, to be able to fully participate. But I think there's something hopeful that comes out of that as well.

Benjamin Law: What about for you, Sam, what have been interesting ways that you've seen younger people, older people, or even people in between, you know, the so-called sandwich generation, who are both caring for other people, both generations. How have you seen the effect on people depending on where they are at stage of life?

Sam Mostyn: I’ll give you three examples, Ben. So my daughter has the triple whammy, my gorgeous daughter, she lives in Melbourne, so she's been through the Victorian lock downs. She is a creative, so she's in the arts sector. And she wants to think positively about the future, but can't be with anybody. And in that, in that environment, Melbourne, at the moment, just as is in Sydney, this kind of self lock down that's going on, so there's just nothing, there's nowhere to go and see, there's no one to be with. And my experience of her life is that the art sector, particularly a lot of young people in the art sector, had no social support, there was no financial support, they weren't caught up in any of the big economic support mechanisms. So she's had to take care of herself, she's got a bit of the bank of mum and dad, but not many young people have that. But having to work in isolation, and keep working on her craft and then cancelling her shows because of the issue of, of now Omicron. And so I think I don't want to speak for her and I shouldn't speak for her. But her experience of it, I would say, that it's hard to be really optimistic and positive when you're looking at a country that didn't look after those young people, her fellow international students that she saw catastrophize in those early days, and then her, her arts practitioner colleagues and friends, in a community that we actually relied on to keep us feeling optimistic, we drew on all the arts to do that. So that mix match, I think, was really interesting. My second perspective is I chaired the Foundation for Young Australians, and we do a lot of work with those young people and the issues of young people and their rent, and where they were living, just being ignored generally, right across those early stages, that the amount of couch surfing the amount of having to move home, just life changing forever, and no real sense of of what the future could hold. But particularly our young people FYA told us, there was no opening to put them into the conversation about what some interesting, innovative collaborative efforts could be to support young people. So the absence in the big commission's that were created, the lack of a young person's voice, several voices from different backgrounds, in those key moments of decisions, because it was a real, a real miss, and felt by young people. And the third thing I'd say is, I was able to spend time in our community organisation, Addison Road at Marrickville, through most of COVID, I continue to go there to volunteer. And so many young people came along to volunteer, because it was a means of actually engaging, and so many of them came from communities in south west Sydney, who wanted to help others. It’s an immediate desire to be part of a solution, to front, to turn up and want to help others that they felt were in greater need than them. So a real sense that, that when allowed, and invited in, respectfully, wanting to help others, and just wanting that same respect shown to them. One of them said to me recently, it's our communities, our supportive communities, and so many parts of those communities, have been young people who've been taking that burden of care for their parents, their grandparents and others. And that's not been recognized as part of, you know, young people have not been really recognized as part of the strength of our future. So, you know, I think we've got a lot of work to do. And back to, if you put care at the centre of our thoughts, we'd be thinking about where all those parts of the system are, that we have been drawing on to provide elder care, disability care, community care, we’d think differently about policies, I think, and we still think differently about the stories that we need to hear from our leaders about what an optimistic future looks like, that brings everyone along.

Benjamin Law: Thank you Sam, and thank you for that reminder, as well, in that, in all of this, where we sometimes feel helpless, on a big picture level when it comes to you know, federal politics, that a lot of the movement and substantial change can be made within our own communities and backyards as well. I'm a big fan of what Addison Road does. If you want to find out more, you can go to addyroad.org.au. I'm gonna throw it over to the audience now. We've already got some questions coming in. So keep them coming through. I'm going to start with a question from Jane H, who says that governments in particular, their decisions are so short term. This is really growing off what we were talking about before. Nothing seems to be focused on long term solutions. How can we make them see sense? I mean, I guess one answer is an election. I'm curious to hear, how do we actually communicate our needs better with the people who actually call the shots?

Sam Mostyn: I think we've got to demand more of our leaders. We've got to demand that… and it comes back to this trusting democracy, trust in our institutions. I think we're yearning for long term pictures of what the country could be. We're yearning for policies, we won't see the impact in the short term, but we will… we have confidence around the long term. And before COVID, the best example was climate change. And Richard’s referenced that a couple of times. Everyone is feeling, already,what the long term impacts of climate change are going to be for us, because it's become short term because of the dramatic change in our climate system. And I don't think anyone, I don't think many people would be concerned if we heard governments talking about really active, positive, long term targets that say, we want to beat those targets, because that kind of, that casting of a big, big hairy target for climate that we then have to work with, encourages us to be innovative, it drives industry, it drives behaviour change, and we actually feel we’re part of a collective response to those long term issues. I think it's the same with early childhood, same with gender equality, it's the same with, much, much more engagement with our multicultural communities. There is a long term story of something where we're having… we're hearing from our leaders. I don't know how we make it happen necessarily then other than electorally, but I think their risk aversion, back to the lack of courage, misreads the community's sense of wanting to be part of a long term story about the future.

Benjamin Law: And Richard, I'm going to throw you the next question, which is very specific, and in our news cycle at the moment, because Western Australia has decided that their borders are going to remain closed for the foreseeable future, in terms of the actual goalposts of when they might reopen them again, that they're still TBC, some of them. So the question from one audience member is, what impact will the extended closure of Western Australia have on us as a nation? And I guess the extension of that is, what might the impact be on Western Australia itself?

Richard Holden: Yeah, I think it's a good question. I'm quite hopeful that the extended impact will actually be very little, I think, you know, what, what we've seen is, WA has basically figured out, they got themselves into a position where they could, roughly speaking, keep COVID out, at least so far, more or less, and that they actually didn't really need all that much from the rest of Australia, obviously, their slice of the GST revenue, but they also produce quite a big slice of the GST revenue, it turns out that domestic tourism has sort of held up their tourism sector pretty well, as in within WA, tourism. So you know, right now with a very high, you know, iron ore and other minerals prices, you know, I think, WA has been able to weather things, I think long term, there's no reason to think that it should threaten the Federation or anything like that. And I don't think it should have any long long term impact, sort of related to that, and sort of cheating a little bit, coming back to the previous question. I think I'd say that, you know, you and Sam said, you know, exactly right, which is we need to, sort of, hold politicians more to account at elections. I think the other thing is, we can all do something, as voters, as the electorate, in being a little bit less polarised, and a little bit less partisan about things. You know, if you're a liberal voter, actually turns out, some people in the Labour Party have good ideas from time to time. And if you're a dye in the wool, Labour voter, or Greens voter, if a member of the coalition says something sensible, or does something sensible, you know, it's fair enough to recognize that. And I don't know if I'm yearning for an easier time, just getting old, and trying to think back to, you know, 20 years ago, but I felt like things were always pretty tough and always pretty partisan, but things have gotten more so here, and I lived for a decade in the US, and if you want to see how dysfunctional a great democracy can get, you only have to look, look at basically, Australia as been about 15 years culturally and politically behind the US on some dimensions, to see where that goes, and I really hope that we don't go there, and that we can be a little bit more open to good ideas coming from across the political spectrum.

Benjamin Law: Thanks, Richard. That's a really good point. Hey Sam, staying on the closure of Western Australia, to the rest of the country, and Richard’s talking there about the economic impacts. I wonder if there's other impacts as well. I mean, not just Western Australia, but the hard closure of borders between states and territories for such a long time now, do you foresee long term impacts, I guess, on our understanding of Australia, the way that Federation works, the power that Premiers and Chief Ministers now have, and the way that national cabinet now works? What's that done to our understanding of Australia itself?

Sam Mostyn: That's a great, complex question. I think we've learned that running federations is difficult. That we like to think of ourselves as Australians, but actually, many people do think of themselves in a much more parochial fashion and look to the local, the local state leadership, and even local council leadership, for their sense of place. I think it's thrown up, something that Richard was, I think, alluding to is, if you want the Federation to work well, we've got to find a way beyond this partisan nature of politics, and government. So the idea of collaborative effort and the Commonwealth working in partnership with governments, irrespective of political hue, is a really important thing for us all to learn. I think it's a really important factor for us all to have confidence in our Constitution, our democracy and the Federation, that you can put aside the political stripes and actually work for the betterment of the country. And I think the West Australian outcome is one of the Premier at the height of his power is reflecting what many people in Western Australia are demanding, which is don't open up, because we actually feel safe, they don't feel abandoned by their Premier, they don't feel as much as part of Australia. But I guess there were specific instances of missing family and family reunions and those kinds of things. But generally, what I've heard out of WA is, don't make the East Coast mistake of assuming that that decision isn't actually playing very well locally. And so, you know, that would say that something has gone wrong with the, how we think about the Commonwealth and Western Australia. And we joke about secession and all kinds of secession, sorry, it does point to an underlying problem, I think, that we've got to have leaders who are happy to put aside the political stripes and work together, and give confidence no matter what State or Territory we're in. That would be a really great use of our federation and the Constitution. And our constitution is designed to be a very flexible, dynamic document to help us get there. So I'd hoped that we could do more of that.

Benjamin Law: Thanks Sam. Hey, Richard, I'm going to throw the next question to you from Arne and M, the Australian Government, balancing public health care and economy with the Omicron wave, how can this balancing be improved? I guess that touches on things that we've already talked about, but I guess if you had the government's ear, are there, you know, practical considerations, practical policies, even that you'd recommend in seeing that that balance be addressed?

Richard Holden: I think practical is the key word there. So I think that we saw, you know, unfortunately, in New South Wales, a degree of triumph of political messaging and ideology over pragmatism when it came to the way we did our reopening. So, you know, there was a date in the calendar. And, you know, it seemed that a political brand had been tied to that, in the case of the Premier, and you know, we were going to reopen regardless of the circumstances. Now, even if that was going to happen, one would hope that that could be done in a sensible way, where some of the just really low costs, not costless, but really low cost measures were in place. So keep mask mandates in shopping centres, you know, maybe don't open nightclubs and things like that. Now, that's a cost to some people, it's a cost of nightclub owners and so on, they could be financially compensated, none of these things are free, if they were free, they'd be no brainers. But, I think just doing the low cost, sensible things, well, and you know, one of the biggest things that Sam's talked about, and you've talked about it is, you know, purchasing of rapid antigen tests, that people were talking about in 2020, about the need to do this. Business community were very vocal about it in August of last year. You know, I got very frustrated with the TGA, not approving these things and wrote in The Financial Review about that in August last year, lots of people were saying it, it was on the radar screen, it was entirely predictable, that this was going to happen, and yet somehow nothing happened. And so, I think it's a combination of being forward looking, and also just, you know, trying to think about things through a practical and pragmatic lens rather than through a political branding exercise.

Benjamin Law: Well, Sam, what we're talking about practical and pragmatic, the next question taps into this. How do you see us as a nation resolving the gendered issues that we've already discussed, within the care sector and with female underemployment? Again, I guess, this is a chance to discuss about practical and pragmatic policy, things that could be implemented here. Do you have any recommendations, any hunches?

Sam Mostyn: I’m going to go in two directions here, because it's a wonderful question, Ben. The first is just, we shouldn't forget that last year, 2021 was a reckoning on women's issues on a very grand scale. So it wasn't just our employment, it was our safety, it was the respect for us at work. Kate Jenkins, she would give reports on the lack of safety, not just for women, but for anyone different, really, in workplaces across the country was devastating. And we've got those recommendations about how we need to have real commitment to respect at work, and good employers are already doing that. And then we had the investigation as the parliament where we'll see the response to that in the new year, or as part of the return to the parliament. So safety and respect are very clear things that, if women don't feel safe in the workplace, then it's hard to encourage women to go into those workplaces. So we've got to have a system that makes sure that all workplaces are safe for everybody. That's both legislative and behavioural, and leadership right across our country in every workplace. So that's… we'd have a big talk about safety and domestic violence, and all those things that became so much more profound during COVID. But, to the point about employment, and women's equality in this country, I think they're really, really serious, very simple, practical things. It does go to the fact that we’re heading into an election, you can ask anyone who's standing for an elected representative position, what they believe their policies are that go to the full inclusion of women, you can ask them how what they believe about gender equality, you can ask specific questions about their commitment to respect at work, to setting targets for women in leadership, to understanding what it is that holds back women. And then you can ask them a question about their beliefs and their commitment, practically, to early childhood education and care, and to paid parental leave, and all the systemic things that only government can actually do for us, which is to make those big policy changes in the interests of both the country and the full utilisation of women and men and anyone who's involved in care. That sort of would send a message that this matters, to people who are interested and who represents us. And the last thing I'd say is we've got to, I think we've got to support more women in our political system, I think we've got to have many more women at the table when decisions are made, and when policies are made, whether they're elected representatives or not, just include us in the discussion, we actually do understand how communities work and often have gems of information about practically how things get done. How vaccination could probably be done at schools really effectively. We're facing at the moment, I think it's about 60% of parents across the state and across the country are feeling very nervous about the opening of schools. And of course, that immediately impacts women's sense of whether they can go back to work or not. So the practical issue would be to call on governments to be very clear about school reopening. And to Richard’s point, don't make a political decision, make the right decision for families in the environment we're currently in. Last thing I'd say, we have got to look at the feminised industries across our country, that sit largely in care, and not just take the findings of the Royal Commissions into what then happens with compromised care, but care about those people who work in our care sectors, predominately women. And think about, how do we pay? What are the terms and conditions? How do we really thank and reward those that do our caring? They are practical things we could do today, but it means owning up and facing into the issue that this is a workforce that has been, as you said, underappreciated, underpaid, and often not paid. And so, I think that's a big part of the story. And I think it would be great for the economy, to actually encourage people to want to work in the care sector, if we had the right workforce conditions and workforce plans, I think we could be very proud of that, if that was something we could do as a community to demand the care at the centre of our economy and measure it properly.

Benjamin Law: Thank you, Sam. We are almost out of time. But just before we let everyone go, we've been talking a lot about the costs, which are real tangible and felt across the community. And so you Sam, you said right up at the top of the session, that you're losing that sense of optimism, which is a whole other discussion that we should have at the pub, actually, after this session, in a safe and socially distanced way. But I'm keen to leave on a sense of hope, as Harvey Milk, the gay rights activists said, you've got to give them hope. And I am curious, not in a Pollyanna, not in a naive way, but what are the causes for optimism for each of you at the moment? Big picture or community level, that we can take into the year ahead and into the future? I'd like to start with you, Richard, what's a cause for optimism for you?

Richard Holden: I think we've come out of the pandemic or are coming out of the pandemic, learning that government really can be a force for doing very good things. We've learned that government can spend hundreds of billions of dollars to deal with what could have been the greatest, you know, financial disaster in a century, and can be very effective. We've learned the government, when it gets things right, with vaccines, and things like rapid antigen tests can be an enormous force for good in terms of coordinating a national effort towards things. So I think we've seen what government can do right, we've learned some lessons about how we could improve. We've basically seen what government can do,And we've seen, even on the conservative side of politics, that government can be seen as a force for good. And I think that's incredibly positive.

Benjamin Law: Sam?

Sam Mostyn: Yeah, I agree. I share Richard’s optimism on that level. I think there was lots for us to learn and take heart about when government does act in the national interest, in the public interest, it can do remarkable things. I think the private sector has changed dramatically as well, the organisation's I’m part of have stepped up and really do believe at the core of being a profitable and well supported organisation, is a commitment to very strong social and environmental values. We have seen the rallying of markets around the world, trillions and trillions of dollars going into solutions to climate change. We're seeing the same thing, I think on respect at work. There's been a general uptick in, I think, leaders in the private sector or running organisations, not just private, working collaboratively, across civil society with government trying to solve things. And I'm very enthusiastic and encouraged by that. And the last thing I'd say is we did really get to know a lot about our neighbourhoods, and about community, and I got to meet people and spend time with people I've never met before that are in my local community, who will be great friends. And we've learned how to actually support one another, that we were probably ignoring, before we were forced to look locally and really care for one another. And of course, we've learned a bit more how important care is in our society, and that can only be a good thing.

Benjamin Law: Sam Mostyn, Richard Holden, thank you so much.

Sam Mostyn: Thank you.

Richard Holden: Thanks, Ben.

Benjamin Law: Thank you. And thank you all for joining us here. If you're watching us on the live stream, thank you for joining us on a Saturday afternoon here at Sydney Festival. Just before we wrap up a final word. Some of you might be aware, or have seen in the news that there have been calls to boycott Sydney Festival. And you might have also read that I recently resigned from the Sydney Festival board which is true, but obviously it's a festival I love and I'm participating in it today. And I do feel that sometimes context is missed in the conversation around these boycotts. So I will give some here. The Sydney Festival approached the Israeli embassy and received funding for the support of a production of a dance work at Sydney Festival which has now been completed. And this funding was arranged during a period in which fighting between Israel and Hamas alone with over 200 people dead in Israel and the occupied territories, and majority of them Palestinians killed by Israeli airstrikes in the Gaza Strip. A full statement explaining my position and context is on my social media accounts, and for what it's worth today I'm donating my fees from this session to the Palestinian Children's Relief Fund. You can read more about their work and how to donate by searching for Palestinian Children's Relief Fund or heading directly to pcrf.net. And if you want to find out more about the Australian context for these conversations, you can learn more at the Australian website dobetteronpalestine.com. Thank you so much for your time. And thank you for joining us here at Sydney Festival.

UNSW Centre for Ideas: Thanks for listening. For more information visit us at sydneyfestival.org.au and centreforideas.com. And don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Richard Holden

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Sydney and President of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia. He was formerly on the faculty at MIT and the University of Chicago, and earned a PhD from Harvard University. He has published numerous papers in top economics journals and is a regular columnist at The Australian Financial Review.

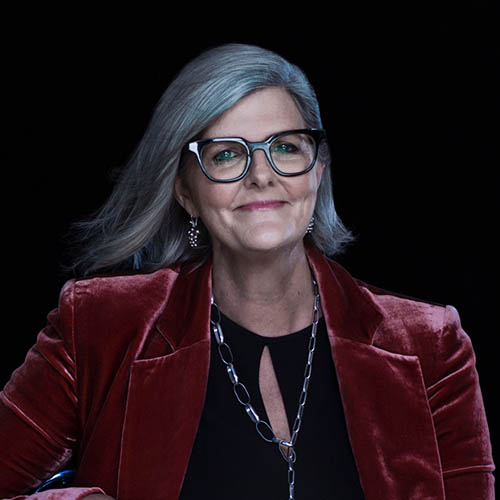

Sam Mostyn

Sam Mostyn AO is a businesswoman and sustainability adviser, with a long history of executive and governance roles across business, sport, climate change, the arts, policy, and NFP sectors. Sam is the President of Chief Executive Women. She serves on the board of Mirvac, is the chair of Citi Australia’s consumer bank, and chairs the boards of the Foundation for Young Australians, Australians Investing in Women, Ausfilm, ANROWS (the Australian National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) and Alberts.

She also serves on the boards of the GO Foundation, the Centre for Policy Development, The Climate Council, Tonic Media, and until recently as an inaugural board member of Climateworks Australia, and was a Commissioner with the Australian Football League for over a decade until 2017.

Previously, Sam has served on the Global Business & Sustainable Development Commission, and on the boards of Reconciliation Australia, the Australia Council for the Arts, the Sydney Theatre Company, Sydney Swans, Transurban, Virgin Australia, Australian Volunteers International, and has chaired Carriageworks and The Australian Museum.

Benjamin Law

Benjamin Law is an Australian writer and broadcaster, and is the author of The Family Law, Gaysia: Adventures in the Queer East, the Quarterly Essay Moral Panic 101 and editor of Growing Up Queer in Australia. Benjamin created and co-wrote three seasons of the award-winning SBS TV series The Family Law, based on his memoir, and wrote the sold-out mainstage play Torch the Place for Melbourne Theatre Company. In 2019, he was named one of the Asian-Australian Leadership Summit’s (AALS) 40 Under 40 Most Influential Asian-Australians – winning the Arts, Culture & Sport category – and one of Harper Bazaar’s Visionary Men. He has a PhD in creative writing and cultural studies.